It quickly became clear that treatments of mental illness varied enormously around the world. So, we began to look at the raw statistics of treatment outcomes – essentially, what worked and what didn’t.

This is partly a funding matter, but it’s also true that some systems work better than others.

To our horror, we discovered that the UK and the US – the two countries where Joshi sought and received mental health treatment – are a long way from being the best places to suffer any form of mental illness.

The US, for all its wealth, technological innovation and medical advances, is almost certainly among the cruellest, most ineffective and worst places in the world to be mentally ill. The UK, meanwhile, lags significantly behind most of its European neighbours. We thought we were being offered the best support available. It wasn’t true.

Too late we discovered fully functioning mental health systems that produced consistently impressive outcomes – such as Finland’s “Open Dialogue” methods, as well as successful awareness and treatment efforts like Luxembourg’s “Positive Education” programme and Germany’s easy therapy access and financial support for patients with mental illness.

Then we found Trieste – probably the best place in the world to have a mental illness. Not only did the Trieste model outshine everyone else in terms of successful treatment outcomes, its therapeutic focus on the individual’s immediate and long-term needs, means that commitment and compassion are built directly into the system itself. If only we had known earlier.

It struck us almost immediately this was exactly what Joshi needed – not pharmaceutical after pharmaceutical, or box-ticking, once-a-month therapies that never worked, but rather a system of care that could get to the heart of her mental illness and help her find inspiration and her place in the world around her.

Of course, Joshi is not alone. Tens of thousands in Scotland, and millions around the world, suffer as she did. And neither are we alone: our tragedy, the loss of a child, is perhaps the oldest and deepest sorrow known to our species.

Why then is the Trieste model of mental health treatment, a model of compassion, dignity and documented success, not implemented in every community, in every country in the world? This is our long-term ambition.

A Little History...

In the early 1960s, the famed Italian psychiatrist and revolutionary reformer Franco Basaglia began a mission to try to transform and then close down mental asylums in Italy. His radical idea was that when individuals are deprived of their human rights and dignity, recovery from mental illness is impossible.

Freedom itself is therapeutic, he asserted years later.

Basaglia’s work led to the abolition of all asylums in Italy – called Law 180, promulgated in 1978, and still known affectionately today as Basaglia’s Law.

The asylum in remote Gorizia, where he began his career, took him “straight back to the war and the prison," he said. Basaglia had spent several months in jail for his anti-fascist protests against Mussolini.

Under the existing system of psychiatric care in Gorizia, across Italy, and around the world, he concluded, psychiatrists were closer to repressive prison guards than humane doctors.

As director of the Gorizia asylum, Basaglia eliminated the straitjackets that some patients were forced to wear, removed bars from windows, prohibited electroconvulsive therapy and abolished isolation as a treatment-response and a punishment.

Basaglia at this time was also fascinated by the work of psychiatrist Maxwell Jones in Scotland. Jones was the Physician Superintendent at Dingleton Hospital, the former psychiatric facility in Melrose, in the Scottish Borders.

As the father of the “therapeutic community”, Jones was making his own efforts to transform the asylum system in the UK, and Basaglia is known to have visited him. Both men were wary of changes in hospital organization and management that did not operate for the purpose of asylum patients’ liberation and their autonomy in the community, that continued to hold people against their will.

Basaglia’s ideas crystalized in the early 1970s in the north-eastern Italian port city of Trieste, where he gradually closed the asylum and replaced it with a comprehensive alternative community service, a combined it ground-breaking therapeutic principles and individualized recovery models.

The establishment of Basaglia’s model of mental health treatment in Glasgow would, somewhat poetically, bring his vision full circle, back to Scotland.

A Revolutionary Recovery Model

Today, Basaglia’s legacy – he died young in 1980 – is known as the “Trieste Model.”

It is a system of “social” psychiatry based on a simple idea: people disabled by mental illness, whatever the diagnosis or severity, are as deserving of the same human rights as everyone else. They are citizen of our societies.

From this basic idea, all else flows:

- Respect for the individual’s dignity, as well as the legal recognition of their civil and social rights;

- Empowering people with the right to “negotiate” their own treatment and recovery, according to their own circumstances and personal needs;

- The right to work, to education, to access to their community, along with all of its social and support networks, and to have relationships;

- The profound, if obvious, realization that while all care and treatment should be individualized, people cannot recover in isolation.

- The community, and the society at large, must change its thinking about ill mental health and abandon all stigma and discrimination.

- Thus, by extension, the Trieste model places the suffering person — not his or her disorders — at the centre of this unique, holistic mental health care system.

Based on these basic tenets, the emphasis of treatment is focused entirely on an individual’s personal story, their specific and immediate, whole-person needs, the integration of care into their life and aspirations, and their recovery through the rebuilding of relations with the community.

All treatment and care are provided through the access point of the Community Mental Health Centre (CMHC), as described above in our proposal for an NHS-operated pilot centre in Glasgow.

Four CMHCs operate in Trieste, covering a population of around 240,000. These serve as access points and community hubs for the planning, care, therapeutics and the social focus of the mental health system.

Families and friends are welcome in this environment that is creatively designed, relaxed, friendly and attractively furnished. No white coats are allowed. CMHC staff and service users are indistinguishable.

The CMHCs, as well as the person’s home, are where initial psychiatric evaluations, understanding the needs of care and development of trustee relationship take place. The CHHC is also where daily lunch is served – to which family and friends are invited and encouraged to become part of the care, treatment and social engagement.

These centres also create social, recreational and work opportunities, promoting a social network of friends, family, neighbours, staff and volunteers, who are a key part of the therapeutic process of social reintegration. Rehabilitation and recovery are promoted through cooperatives, expressive workshops, school, sports, music, theatre, recreational activities, youth and self-help groups.

A System that Works

To the surprise of critics of Basaglia and the paradigm of comprehensive, whole person care he and his followers created, the Trieste model has consistently delivered better long-term recovery outcomes for individuals than any other form of mental health treatment.

And for more than 40 years, Trieste has not had any kind of specialised mental hospital. The asylum was replaced by 40 different community structures with different roles and tasks.

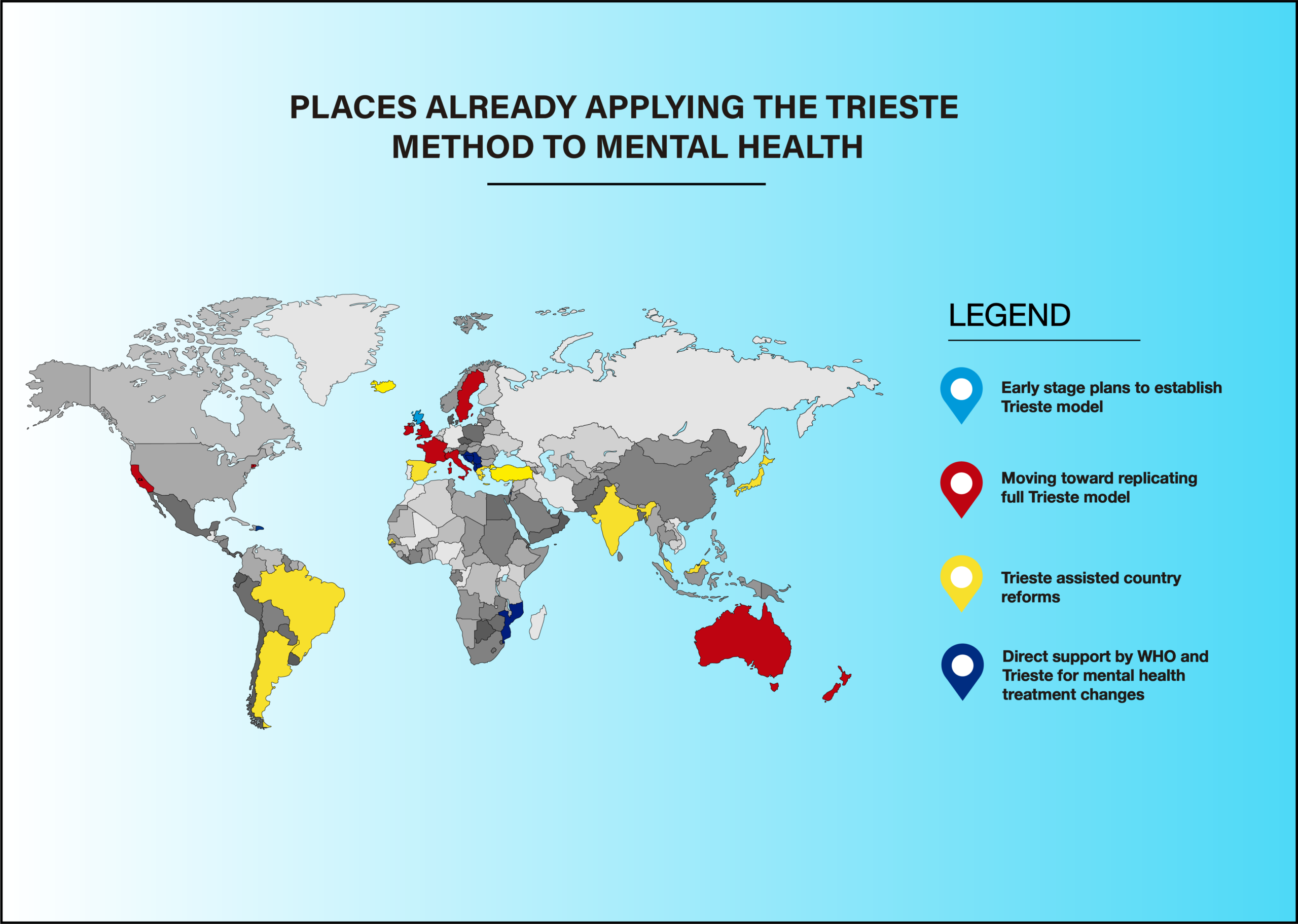

The model has served as a crucible and an inspiration for dozens of mental healthcare projects in more than two dozen countries around the world.

The map above is only a partial representation of places where the Trieste model is being used to change antiquated, disjointed and failed systems of mental health care that are simply not fit for purpose.

The statistics from Trieste speak for themselves:

- Reduced hospitalization rates

- Reduced compulsory treatment rates

- Reduced suicide rates

- Reduced re-admission rates

- Reduced drug addiction rates

- High percentage of people in work, housing, and social inclusion pathways

It’s worth pausing a moment to look a little deeper into the impact of suicide rates in Trieste. They didn’t just reduce, they halved over a 20-year period – an astonishing accomplishment by any standard.

And in recognition of the often-overlooked comorbidity of drug abuse, which regularly goes hand in hand with mental illness, addiction numbers in Trieste have also plummeted.

Dr Roberto Mezzina, who worked with Franco Basaglia and is himself a former director of mental health services in Trieste, recently wrote: “Trieste has demonstrated a different approach to innovative community mental health, moving from a narrow clinical model based on the illness… to a broader concept that places the whole person at the centre of the care system, with the highest attainable level of freedom and respect for their powers of negotiation.”

Dr Mezzina is also working with and advising The Joshi Project on the establishment of the Trieste model of mental health care in Scotland.